We’ve all seen that tag in front of a movie: “Based on a True Story.”

And there’s never any shortage of movies like those. This year alone, there are a whopping 18 of ’em, including several in theaters right now: First Man, Can You Ever Forgive Me?, and Beautiful Boy, as well as several from earlier this year (Adrift, Tag and The Miracle Season, among others.

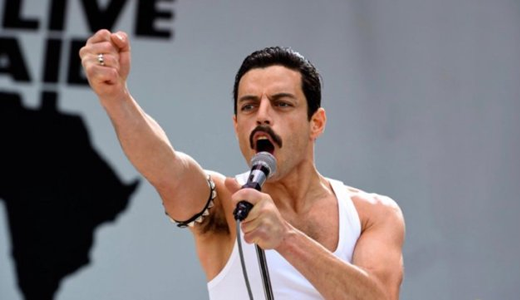

Another big one makes its way into theaters this weekend: Bohemian Rhapsody, the story of Freddy Mercury and his iconic British rock band Queen.

I saw the film last week (and you can find our full review on Thursday). But while researching the movie, I came across an interesting article on Slate that examined how much of the film is accurate, and how much is Hollywood “dramatization,” as filmmakers often like to say. Which is, of course, a polite synonym for fictionalization.

For the most part, the broad brushstrokes of the film are fairly accurate. But the moviemakers did take some liberties with depicting the tragic story arc of Freddy Mercury, who died of AIDS in 1991. The movie uses his diagnosis as a dramatic segue into its finale: Freddy being reunited with his band (after a period of alienation from the other members) for the historic Live Aid relief concert in 1985.

Before the show, he tells them that he has the then-fatal disease, dramatically raising the stakes for their performance. Except, that, well, he didn’t actually make that confession to his longtime bandmates until years later. Slate’s Ellin Stine writes,

This is perhaps the movie’s biggest departure from the facts. It’s widely disputed when, precisely, Mercury contracted the disease—biographer [Lesley-Ann] Jones claims it could have been as early as 1982—but he lived for six more years after the Live Aid performance and didn’t tell his bandmates about his diagnosis until 1989. Taylor recalled Mercury saying, “You probably realize what my problem is. Well, that’s it and I don’t want it to make a difference. I don’t want it to be known. I don’t want to talk about it. I just want to get on and work until I … drop,” and this is what he did. Despite rumors fueled by Mercury’s increasingly gaunt appearance, colleagues and friends continued to deny he was ill, until Mercury released a statement acknowledging he had the disease the day before his death.

Now, the core truth is still, true: Mercury did eventually tell his friends that he’d contracted AIDS. But this particular choice to rearrange Mercury’s biographical facts serves as a good reminder to anyone watching a movie that’s “based on a true story.” True doesn’t always mean true—as in, this is exactly the way it happened. Instead, we’re likely getting a version of the truth that may deviate in some significant ways from reality while still staying fairly “true” to the general story.

It’s a truism we know, of course. Still, there’s something about seeing a story depicted on the big screen that nevertheless influences us to accept the version we see there as the real thing—even if we know better. A good storyteller connects the dots in an emotionally engaging and satisfying way for the purpose of creating a movie that works.

Life, in contrast, is messier. More complex. Less neatly tied up with an emotionally cathartic ribbon. Even lives like Freddy Mercury’s that might lend themselves to a dramatic retelling.

In our time of competing narratives, “your truth, my truth,” fake news, real news and everything in between, it’s good to remember that not everything we see in movies “based on a true story” is actually … true.

Recent Comments