I Still Believe isn’t the only faith-tinged movie playing in much-depleted (and rapidly shuttering) theaters right now. Another film, featuring Oscar-winning actor Forest Whitaker and the talented Garrett Hedlund, was released Feb. 28 and contains deep themes of sin and salvation, judgment and mercy. It even comes with an old-fashioned baptism.

The catch: The movie, Burden, is rated R, and it deserves it. It’s profane, violent and deeply challenging—and director Andrew Heckler says it had to be that way.

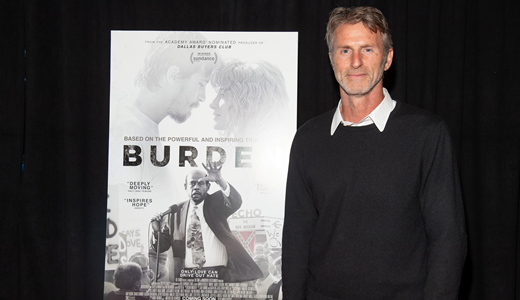

The movie centers on the real-life story of Mike Burden, a hardcore KKK member who helps open up a Klan-themed museum in Laurens, South Carolina, and then experiences a remarkable turnaround—thanks, in part, to some stubborn love and undeserved grace. Director Heckler spent a couple decades trying to bring Burden’s story to the big screen. We had a chance to chat with him about the film’s bumpy journey, about the stubborn racism the film portrays, and why faith was such an important part of the story. And Heckler gave some advice to faith-based filmmakers, too. (The interview below has been edited a bit for both length and clarity.)

Paul Asay: I understand that you first learned about this story in 1996 and ’97, as it was unfolding. And you’ve been working on getting that story made into a movie almost ever since. That’s more than 20 years.

Andrew Heckler: It’s been a long journey. It’s funny. It’s been almost half my life.

I had discovered the story when I was in New York and I was single, and I had a theater company, and I was just fascinated. I could not believe that that kind of overt bigotry and racism could exist in 1996, when they could open up a Klan shop in a small southern town. And then I ended up going down there, I spent a lot of time in Laurens, South Carolina, getting to know the people and getting to know the town and getting to know what was going on down there; getting to know the real people behind the stories. I had written the first draft of the screenplay in 1999, 2000. It seemed like it was on the fast track to get made. And of course that was not the case.

Asay: Part of the problem was the studio you were working with [Relativity Media] went bankrupt, right?

Heckler: There are many incarnations of what happened to this movie. But needless to say, we had a studio that went bankrupt, we had actors coming and going. I like to joke that we had the entire cast of the Avengers attached to this movie.

Asay: But clearly, the story got under your skin. What was it about it that told you it had to be a movie?

Heckler: I just thought that what a heroic thing to do [for those around Burden to help him out of the Klan, and for Burden to ultimately turn his back on it]. What an amazing, brave and courageous thing to do for these people—for all of them to sort of share the burden of pulling someone out of hatred and bigotry and into love and tolerance. It was really through the love of a woman and the faith of a reverend, which is a somewhat of a simple idea, but a very complicated process.

Asay: Would you say that that process makes this an important, relevant story for today, as well?

Heckler: Unfortunately, it’s as relevant as it ever was. We’re at a point where no one’s even listening to the other side anymore. We’re just off in our own corners with our eyes closed and our ears plugged. We don’t want to hear anything, we don’t want to discuss anything, we just want to call names and that makes it easier. And that, literally, is what is going on today. I want to force people to treat people as human beings, to see people they don’t want to see. Open their hearts. As hard as that is right now, if you’re able to do that, the end result is that you can turn a horrible situation into one of love, faith and tolerance.

Asay: The message at the heart of the movie, that difficult message of forgiveness, can be a hard one to convey right now.

Heckler: Forgiveness is sorely lacking in the world today, and Forest said it really well on stage the other day. He said, “It’s not just about forgiving the other. It’s about forgiving yourself for having those feelings in the first place. Start there and work on forgiving the other.” And I thought that was awesome, because he’s right.

Asay: I heard that some pretty crazy things happened during the filming, did it not? Stuff that suggested that, more than 20 years after this story took place, racism is still very much a part of our world.

Heckler: We had some really extreme incidents where we realize that the Klan was alive and well down in small-town America, not to mention big-town America. We had people coming on set and throwing Klan [tokens] at some of our African American actors and hair and makeup people, and that was pretty scary.

We had to build the KKK museum in this town [Burden was filmed not in Laurens, but in a small town in Georgia], and almost right away, I got a call late, late at night, from my production designer. And she said, ‘You have to come back to the shop.’ And I said ‘I’m exhausted. I’m almost home. I have a big day tomorrow.’ And she said, ‘No, no, you have to come back now. People are shopping. And that didn’t happen once. That happened all the time we had that shop on the square. It was pretty indicative of what was going on here.

But you know what? I was being interviewed yesterday in a restaurant, a fine dining restaurant in Chicago by an African-American reporter. And I said, ‘You think this is systemically only in the South? Why don’t you look around this restaurant right now and tell me what you see.’ And he looked around and said, ‘I’m the only black guy here.’ That’s a different kind of racism.

Asay: Working for a faith-based organization, I was really struck by how much this felt like a Christian film, in a way. But you couldn’t really tell this story without dealing with faith, could you?

Heckler: When people ask me what [the film’s] about, I say, ‘Well, it’s about a guy who’s steeped in bigotry and hatred, and he’s brought over across the chasm to acceptance and tolerance through the love of a woman and a faith of a reverend.’ It’s a movie, frankly, that we found that faith-based audiences really gravitated towards. Yes, it has bad language. And yes, it has some violence, obviously.

When we first screened it in Sundance [Film Festival], I had no idea that there was a faith-based audience that would respond to this movie based on the nature of the material. But we were called into a [faith-based] group called Windrider. And this woman stood up and the first thing she said was, ‘I’m so happy you made this movie, and I’m so happy you made it the way you made it. Because the Bible wouldn’t have been G-rated if you made it today. We’re ready for this kind of film, we’re ready for the truth. And these pandering faith-based movies that most people are giving us don’t ring true anymore.’

I’ve now been to Notre Dame, and I’ve been to several other Christian universities talking about the movie, and what’s really interesting to me is to hear all of the theology that [attendees are] bringing to the table. I wrote the movie about this beautiful story, but I don’t have the depth of knowledge that some of these students have. And they’re really bringing for me. It’s amazing to hear them talk about the film.

Asay: With that in mind, what advice would you give today’s faith-based filmmakers about making a resonant movie?

Heckler: Tell stories that are meaningful to you. If they have to embody faith-based subject matter, then tell them, and tell them honestly. I think that’s for everybody: You tell what you’re passionate about. And if you’re passionately Christian, you should tell Christian stories. But don’t sugarcoat them. Don’t tell stories that you think people want to hear. Tell the story you need to tell. And audiences will find it.

Recent Comments