This is the second part of a three-part series examining the connection between our entertainment/media culture and mental health, the latter of which is a growing problem for America’s youth. Last week, Kristin Smith discussed how celebrities are increasingly open about their own struggles with anxiety and depression, giving their fans permission to do the same. This week, we focus on entertainment itself, and how it can impact our view of mental health in both positive and negative ways.

**

TV can mess with your mind a little. I know.

Almost exactly a year ago (May 18), I sat down to watch the second season of Netflix’s 13 Reasons Why. All of it.

If you’re familiar with our television reviews, you know this sort of complete coverage isn’t something we do very often. Honestly, our small staff just doesn’t have time to comb through every single episode of every single show. But 13 Reasons—given its high viewership, intended audience, and the controversy surrounding it—felt like an exception. For us to get it right, we had to see every single second. And because teens were binging it at the same time we were (no advance screeners for us), we needed to binge, too. I needed to watch all 13 episodes—and write our thumbnail reviews for all 13 episodes—as soon as I possibly could.

I hadn’t pulled an all-nighter since college. But I did that evening.

By 2 a.m., I was feeling the weight of the show. The second season of 13 Reasons deals with a bevy of heavy and sometimes horrific issues, from sexual assault to traumatizing instances of bullying to the ongoing grief left in the wake of a suicide. And I’ll be honest: It was hard for me to watch. I had aged well beyond the show’s intended audience (teens, presumably, despite its TV-MA rating). But I still remember high school well enough to recall the overcharged emotional atmosphere we all felt walking through the halls: how classes took a backseat to cliques and conflict and our own desperate insecurities.

My own personal relationship with depression made me both more empathetic with, and more vulnerable, to the stressed, depressed characters on screen. The combination of too little sleep, too much coffee and the show itself made me feel raw and despondent. It was a relief when each episode ended and I could turn from watching to writing;to review each episode—to ease into the familiar territory of encapsulation and swear-word counting—was strangely cleansing. A way to flush out what I’d ingested, to put the stories and images I’d seen on screen into some perspective not just for Plugged In readers, but for myself.

I made it through, of course—very tired and feeling a bit in need of counseling myself, perhaps, but otherwise fine. But I was also thankful that I hadn’t binge-reviewed the first season of 13 Reasons Why in the same way. Given that that first season was more tightly focused on suicide, and given my own issues with depression, I wondered whether the aftermath would’ve been harder.

Indeed, psychologists believe that the show impacted some of its viewers mightily. Calls to suicide hotlines spiked in the wake of its Netflix drop date—a positive result, most would agree. But online searches related to suicide—people not just looking for help, but how to commit it—rose, too. And just a few weeks ago, a study found a weak-but-alarming correlation between the show’s run and teen suicides themselves.

Mental health is already a huge issue in the United States. But how it’s portrayed in entertainment—and how it impacts real-world issues—adds an interesting wrinkle.

Mental Health Screenings

Not many of us like dealing with mental health issues. But entertainment loves them. Hamlet pretended to be crazy in Shakespeare’s play. Cervantes’ Don Quixote really was. Even further back in history, and you’ve got Oedipus Rex—a Greek tragedy first performed in 429 B.C. based on a myth that Sigmund Freud later used to coin a psychosexual condition.

And as we’ve moved from plays and books to television and movies, we’re as likely to find entertainment in mental illness is as ever. One of my favorite classic movies, 1944’s Arsenic and Old Lace, features two nice old ladies who kindly kill their visitors and their brother, who thinks he’s Teddy Roosevelt.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KPAnWhVV5dI

Dissociative identity disorder is the basis for an M. Night Shyamalan flick. Psychosis takes center stage in Shutter Island. Depression is the main subject of As Good as It Gets. And even more mundane forms of mental disturbance become springboards to learn more about key characters at times. Tony Soprano’s regular visits to his psychologist are a cornerstone of HBO’s hit show The Sopranos.

But movies and television shows often misrepresent the diseases and conditions they portray and create alarming stigmas for those suffering from them. Psychologists lambasted the Jim Carrey comedy Me, Myself & Irene for its comic take on serious mental illness. Silver Linings Playbook, an Oscar-winning dramedy featuring Bradley Cooper and Jennifer Lawrence, suggests that depression and bipolar disorder can be fixed through love and dance competitions. Critics of Girl, Interrupted say Angelina Jolie’s sociopathic character was glamorized.

But these movies, like mental health itself, can be complex—featuring some good along with the bad. While researching this article, I found that Silver Linings Playbook lands on some lists of the “best” depictions of mental illness in film, too. While its cure might’ve been unrealistic, the way the film represented bipolar disorder onscreen was also called both “real and riveting.”

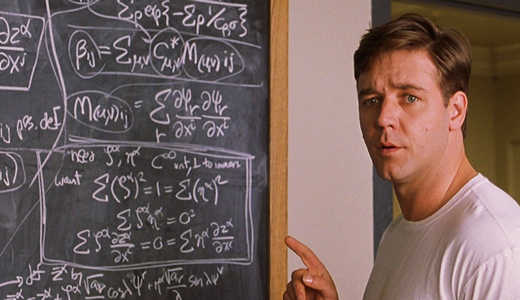

A Beautiful Mind gets double-billing as well. Rtor.org, an online clearinghouse for information about mental health issues, acknowledged that the Oscar-winning film (about schizophrenic economist John Nash) “may have done more than any other popular movie to combat stigma and draw attention to the positive contributions of people with serious mental health disorders.” But it also notes that “people with schizophrenia don’t normally have visual hallucinations,” as Nash did in the film.

Cinema is No Substitute for Real Help

It’s important to remember that storytellers use mental health issues for their own reasons—to spin a compelling yarn—and often don’t let troublesome things like “facts” or “realism” or even “the mental health of its consumers” get in the way. And even when creators try to portray mental health both realistically and helpfully, the message can go seriously awry. We need only look at 13 Reasons Why to see that.

As such, I don’t think that people struggling with mental issues themselves, or even seeking to understand them better, should rely on movies or television for insight. Instead, they should turn to the experts: Mental health professionals with the training and experience to help. Focus on the Family’s website, family.org, offers plenty of resources, including counseling services and referrals.

Recent Comments