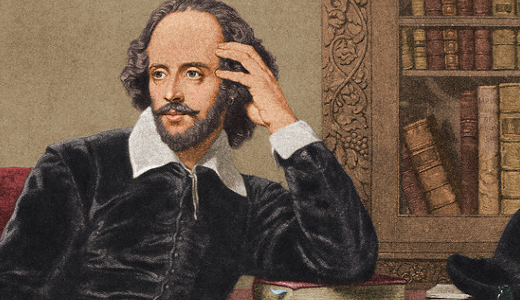

We’re coming up to the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death (May 3). It seemed like a good opportunity to talk about England’s most famous Elizabethan bard, and I was thinking about writing a piece about Shakespeare’s faith: Do his plays and sonnets give us any insight into his spiritual beliefs?

Naturally, my first research step is the same one that any high school freshman takes: Consult Google. Because Google knows all.

So I typed my query: “Was Shakespeare Christian?” Google quickly responded with, it said, 34.8 million results—and at the very top, it gave me a nice little blurb that, Google presumably hoped, would answer my question without a lot of unnecessary clicking and reading. Here’s what it gave me:

In a 1947 essay, George Orwell wrote that “We do not know a great deal about Shakespeare’s religious beliefs, and from the evidence of his writings it would be difficult to prove that he had any… The morality of Shakespeare’s later tragedies is not religious in the ordinary sense, and certainly is not Christian.

Interesting, I thought, but it didn’t seem to jibe with what I thought I remembered from college. So I clicked on the Wikipedia article from which the quote was pulled, and the first paragraph gave me a far different picture of Shakespeare’s faith.

The direct evidence of William Shakespeare’s religious affiliation indicates that he was a conforming member of the established Anglican Church. However, many scholars have speculated about his personal religious beliefs, based on analysis of the historical record and of his published work, with claims that Shakespeare’s family may have had Catholic sympathies and that he himself was a secret Catholic. Other scholars have speculated that he was an atheist. Due to the paucity of direct evidence, no general agreement has been reached.

The article talks at length about Shakespeare’s religious affiliation, the Catholic influences in his life, the Anglican ethos of the day etc. It quotes Shakespeare’s will, which says in part, “I commend my soul into the hands of God my Creator, hoping and assuredly believing, through the only merits of Jesus Christ my Saviour, to be made partaker of life everlasting, and my body to the earth whereof it is made.” Theories as to Shakespeare’s supposed atheism are summed up at the very end of the article in four paragraphs (including the Orwell quote)—lumping it in with speculation that he might have been a pagan, too.

Is all of that stated information true? Some of it? Certainly Shakespeare was an enigmatic guy (some people don’t even believe he wrote those pesky plays of his) and it doesn’t seem that we can know with certainty what, exactly, he believed in. But it would seem that Orwell’s take isn’t the whole story. Woe to the high school freshman who stopped searching after that little Google box.

Now, I’m not necessarily suggesting that Google algorithms—or the bright folks behind them—want to promote atheism or denigrate Christianity. But it is an interesting example of one of the strange dichotomies we face in the information age.

“Knowledge is power,” said Sir Francis Bacon (a man who some, incidentally, believed to be Shakespeare). And the Internet gives us access to more knowledge than ever before. It was thought that the Internet would democratize knowledge: Instead of relying on gatekeepers to tell us what they think is important—teachers, governments, the media—now we, the people, had the keys. We could drink deeply from the well of wisdom without waiting for someone else to bottle it for us.

But here’s the thing: It’s a pretty big well we’re drinking from. When artist Michael Mandiberg calculated the size of Wikipedia for an art installation, he found that it came to about 7,473 volumes, each around 750 pages long. The table of contents alone ran for 91 volumes and listed 11.5 million articles. Now, multiply that by about, oh, a gazillion, and you have an idea of how much information the Internet holds.

So forget democratization: We still lean on gatekeepers to tell us what’s important. Google and other search engines serve as a collective gatekeeper, even though we rarely think about it as such. Complicated algorithms return articles coders deem relevant to us. And those algorithms—even though they’re constantly honed and refined—aren’t perfect. And certainly an engine’s algorithmic overseers aren’t free from bias themselves.

Wikipedia is another gatekeeper—but it’s not the most reliable source itself. It’s created by just everyday users like you and me, who also have their biases, overt or no. (Ironically, Wikipedia has a massive article listing its own most controversial articles—entries that have undergone, and are still undergoing, huge editing battles.)

We get lots of information from Facebook, Twitter and other social networks, but there our own biases—and those of our friends—come into play. We self-select our connections. We click on what interests us, what emotionally resonates with us. Which is why, I’m assuming, cat videos get more clicks than deep discussions of North America’s socioeconomic climate.

There’s not really a great solution to these broad issues and complications of the information age—at least not one that I can find on a wiki anywhere. But my search for Shakespeare’s faith is a good reminder for me of the importance of not necessarily accepting anything I read at face value. Even if Google might like us to.

Recent Comments